The Patriot Privateers Project

The 2025-26 New Jersey State Society Children of the American Revolution (N.J.C.A.R.) State Project “Patriot Privateers” commemorates the United States Semiquincentennial by raising awareness of the active role the Jersey Shore communities and their citizens played in the American Revolutionary War, including the contributions of privateers and the numerous naval battles and skirmishes that occurred near New Jersey beaches. This project is timed to coincide with America250 activities and add these nautical accomplishments to the pantheon of notable New Jersey Revolutionary War events, such as the “Ten Crucial Days” December 25, 1776 - January 3, 1777, which includes Washington’s Crossing of the Delaware River and the battles of Trenton, Assunpink Creek, and Princeton, and notable battles at Millstone, Monmouth, Connecticut Farms, Short Hills, and Springfield.

N.J.C.A.R. State President William Slavinsky is glad to provide the following content about significant naval actions off New Jersey’s coast during the decade of the American Revolution, 1774-1783. Additionally, with the support of lineage organizations and historical societies[1], the N.J.C.A.R. with the elected officials and administrators of the City of Ocean City, NJ are erecting a marker at Veteran’s Memorial Park honoring the privateers, their sacrifices for and contributions to our new nation, while educating others about naval battles and skirmishes in which they fought for our freedom.

[1] Including, without limitation, the New Jersey Society, Daughters of the American Revolution (NJDAR), the Society of the Cincinnati of New Jersey (SOC-NJ), Sons of the Revolution of New Jersey (SR-NJ), and the New Jersey Society, Sons of the American Revolution (NJSSAR).

What is a Privateer?

A ship privately owned and crewed but authorized by a government during wartime to attack and capture enemy vessels.

The commander or a crew member of such a ship.

The coastal communities of New Jersey played a pivotal role in the American Revolutionary War, spanning 1774 through 1783. Situated between the British-held New York Harbor and Philadelphia, New Jersey’s 127 miles of ocean coastline brimmed with maritime activity from ships of many nations carrying trade goods to ships laden with British military supplies and troops. There were many naval actions and skirmishes during the War; in fact, 10 times as many as land actions.[1] The fledgling, cash-poor new nation of the United States faced a predicament: limited time and resources to build ships and train sailors to engage the mighty British Navy. It was clear that the British could control the important ports of the colonies, and that directly engaging a highly trained and well-equipped navy was almost always a losing proposition. Starting in 1776, the U.S. Continental Congress began commissioning and issuing Letters of Marque that legally authorized privateering.

Privateers were privately owned and armed ships with crews that had government authorization to commandeer enemy merchant ships and goods. There were two types of government authorization. The first was a Letter of Marque issued per voyage that authorized an armed merchant ship to interdict enemy merchant ships. The second was commissioning an armed privately owned ship whose sole purpose of its voyage was to interdict. Privateering had many aims and benefits to the new nation. Privateers sought to harass and divert enemy naval actions, including breaking blockades, disrupting military supply lines, and acquiring pivotal goods and money. The practice also aided American troops by capturing British sailors who could be used in prisoner exchanges.

Privateering had been utilized since the 1200s by Old World governments against their foes. By the American Revolution, the colonists had a century of privateering experience as they had supported the British in the wars against the French in the late 1600s and against the Spanish in the early 1700s. Of note is that the end of these military conflicts caused a plethora of out-of-work seamen yielding the rise of outright piracy with such notables as Blackbeard wreaking havoc on the West Indies trade routes as well as in the colonies. Though the colonial governors had long supported privateers and even pirates as they brought much-needed goods and money into the colonies, by the time of the American Revolution, pirating had waned due in large part to British government actions to stop it and privateers were largely abiding by laws and regulations.

New Jersey was led by loyalist governor William Franklin. It was not until he was branded an enemy of the state and imprisoned in the Simsbury (CT) mines in 1776 that New Jersey passed legislation that allowed for a Court of Admiralty, a necessary body to resolve disputes between privateers and ship owners. Because New Jersey had not passed implementing legislation, the lion’s share of prize ships and cargo moved up the Delaware River to Philadelphia, reducing the opportunity for New Jersey to benefit from the activities of its privateers. In March 1777, Colonel Richard Somers and his militia seized a British brigantine Defiance acting as the “Sea Coast Guards at Great Egg Harbor,” which compelled the state to take immediate action necessary for the disposition of the ship and its rich cargo of molasses, sugar, salt, cocoa, coffee, cotton, and whaling gear. On March 12, the lot was sold at auction at the house of John Somers at Great Egg Harbor, with the state sharing in the proceeds. New laws followed establishing a Court of Admiralty, supporting the activities of New Jersey’s patriot privateers and keeping proceeds close to home.

Privateers provided benefits to the new nation and to their crews and owners. By harassing British ships and breaking blockades, the British naval resources were redeployed away from major American ports. Privateers seized ships, disrupting British supply lines while acquiring pivotal goods for the American war effort. Successful privateers would reap the proceeds of the sale of the seized prize ship and its cargo through government-sponsored auctions, proceeds in which the government also shared. Shares of the prize ships would be offered to the crew, the ship’s owners, and sometimes local militia as well, with additional shares awarded for those injured in battle.

However, privateering came with a terrible risk of being captured by the British, as they considered privateers, despite being government-sponsored, as pirates and instituted harsh punishment. It is estimated that there were 50,000 privateers and 1700 ships employed during the course of the American Revolution, and these included actions along Great Britain’s coast.[2] Thousands of seamen were captured. Some were sent to prisons in Britain with little hope of release. Other privateers were kept in abysmal conditions on British prison ships with other captured Americans. One notable example was the British ship Jersey harbored in New York. Many privateers were among the more than 11,000 Americans who died while imprisoned on this one ship, whereas it is estimated fewer than a total of 7000 Americans were killed in action during the War.[3] A prisoner exchange was never conducted despite the colonists being aware of what was happening. Privateers were not considered regulars in the military, and allowing the release of trained enemy forces was feared. Seemingly, the fate of the ship Jersey prisoners was not just, given their patriotic actions.

Navigating New Jersey’s inlets of shallow water with dangerous shoals required local knowledge and smaller ships, benefiting the patriot privateers over the British. Whaleboats, sloops, schooners, and brigantines were commonly used with crews ranging from less than 10 to 200. The agile patriot privateers could make quick attacks and sneak back into their estuary towns without being successfully followed by the British. The privateers also converted available ships, including captured merchant vessels and pilot boats.

New Jersey patriot privateers included farmers, laborers, fishermen, and whalers, and they were supported by the many shipbuilding towns, including Cape May, as well as by ironworks, including those at Batsto. It is estimated the patriot privateers captured over 600 British ships and caused a total of over 300 million dollars in today’s currency of damage to British commerce. This financial impact, along with the colonies’ refusal to pay taxes, made it financially untenable for the British to conduct the war.

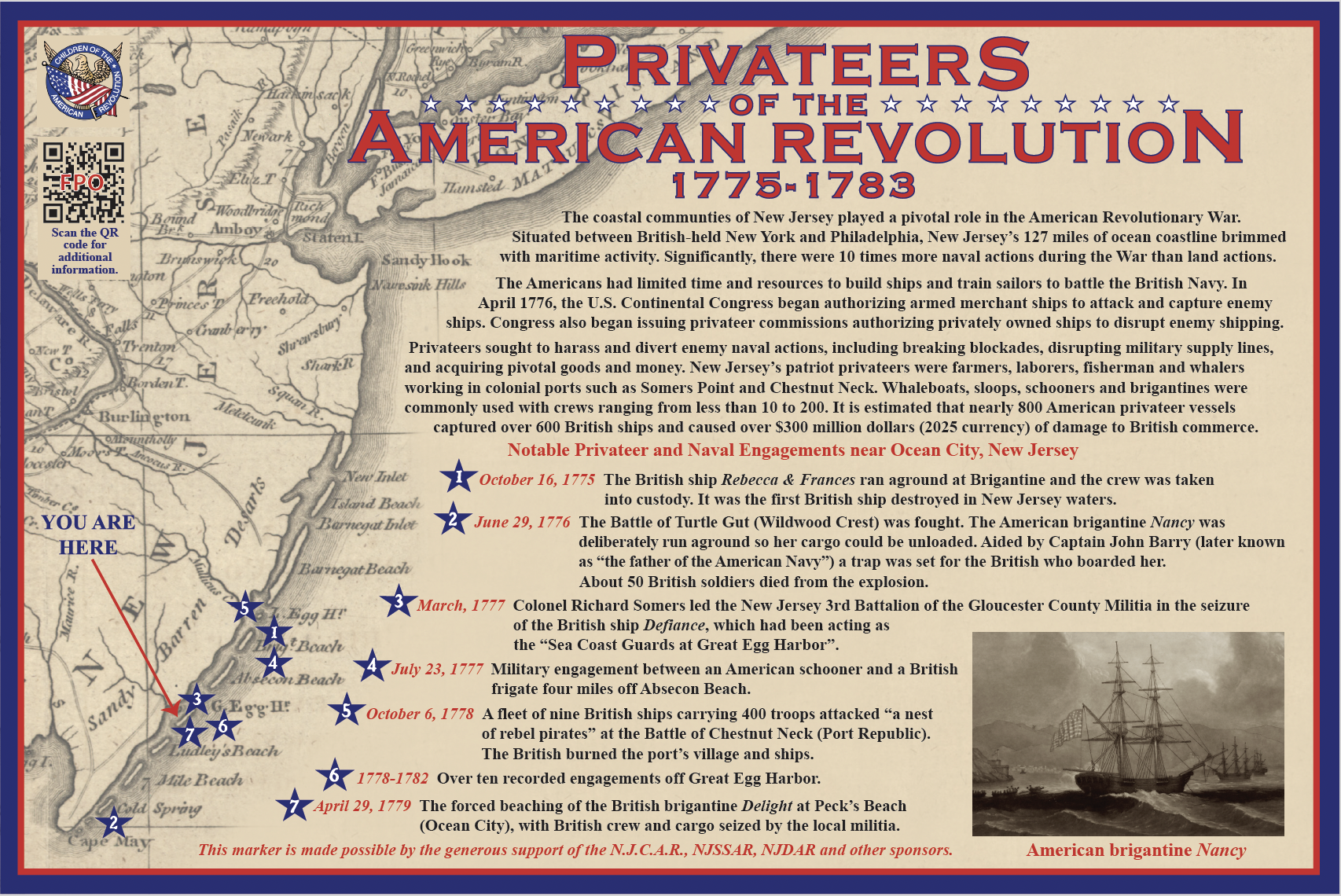

Notable privateer and naval engagements near Ocean City, NJ[4]:

In 1775, the 1st Cape May County Militia was formed, with a 2nd company formed 2 years later. While they saw no local action, they participated in the Battle of Germantown and several other skirmishes. Horseback riders carried local reports to the Board of War, Continental Congress, and the Council of Safety in Philadelphia. A lookout at Cape May was maintained to observe the British naval movements.

October 16, 1775, the British ship Rebecca & Frances ran aground at Brigantine, and the crew was taken into custody. It was the first British ship destroyed in New Jersey waters.

June 29, 1776, the Battle of Turtle Gut (Wildwood Crest) was fought. Two British warships sighted the American brigantine Nancy off of Cape May, which was carrying arms and gunpowder from the Virgin Islands to Philadelphia. Her skipper deliberately ran her aground so her cargo could be unloaded. Aided by Captain John Barry (later known as “the father of the American Navy”) a trap was set for the British who boarded her. About 50 British soldiers died from the explosion.

·March, 1777 Colonel Richard Somers led the New Jersey 3rd Battalion of the Gloucester County Militia in the seizure of the British ship Defiance, which had been acting as the “Sea Coast Guards at Great Egg Harbor.”

July 23, 1777 Military engagement between an American schooner and a British frigate four miles off Absecon Beach.

October 6, 1778 A fleet of nine British ships carrying 400 troops attacked “a nest of rebel pirates” at the Battle of Chestnut Neck (Port Republic). Forewarned of the attack, the town’s militiamen were able to conduct a fighting withdrawal. The British captured only a small amount of supplies, although they burned the village and the ships docked in the port. This was the largest of the New Jersey privateer hubs. In addition to enriching the local community and government, the seized goods were transported overland to supply the Continental Army. This privateering community was crucial in supplying General George Washington’s troops during the harsh 1777-1778 winter at Valley Forge, during the British occupation of Philadelphia.

[1] As described in Norman Desmarais’ The Guide to the American Revolutionary War at Sea, Volumes 1-7, covering naval battles between 1775-1783, published by Revolutionary Imprints (2016), further excerpted at: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/15p6fmXLZqyhWpMEb7p9b9uT2iaDiOCZT/edit?gid=42655462#gid=42655462

[2] Donald Grady Shomette (2016). Privateers of the Revolution: War on the New Jersey Coast, 1775-1783. Page 11. Schiffer Military History Press.

[3] “American Revolution Facts.” American Battlefield Trust, 24 Nov. 2024, www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/american-revolution-faqs#howmanywerekilledorwounded.

[4] David Munn (1965). The Battles and Skirmishes of the American Revolution in New Jersey. Excerpted at: https://www.njssar.org/nj-battles

The National Society Children of the American Revolution (N.S.C.A.R.) is a youth organization that was founded on April 5, 1895. The idea was proposed on February 22, 1895, at the Fourth Continental Congress of the National Society, Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). The organization was promptly chartered by the United States Congress and is now the nation's oldest and largest patriotic youth organization. NSCAR offers membership to anyone under the age of 22 who is lineally descended from someone who served in the Continental Army or gave material aid to the cause of freedom in the American Revolution.

The mission of the NSCAR is to train good citizens, develop leaders, and promote among young people a love of the United States of America and its heritage.

Members gain valuable leadership experience in conducting meetings, following parliamentary procedures and standard protocol, serving as delegates, and speaking before groups at local, state, and national conferences. The responsibility and privilege of selecting officers helps members gain an understanding of the democratic process. Each year, N.S.C.A.R. members develop programs for various projects to challenge members to learn more about their country, including state projects led by the various state organization Presidents.